Why

do outbreaks occur

and what brings them to a close?

Density dependent mortality

factors. Density

dependent mortality factors that

limit population expansion of forest tent caterpillars are the

following:

|

|

|

| Furia gastropachae

a

fungal pathogen (The crustose coating of

conidiophores on the caterpillar pictured above is often absent)

|

Killed by the fungal pathogen |

Nucleopolyhedrosis virus |

The caterpillars to the right are the

indirect victims of starvation. The larvae defoliated the entire

forest

then wandered about for days in a fruitless search for food until they

were overtaken by a pathogen and killed. The most likely

pathogen is Furia whose

spores accumulate on the ground and are picked up by the wandering

caterpllars.

|

|

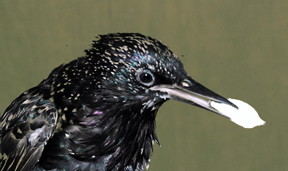

This starling is feeding on the pupa of a forest tent caterpillar. Starlings will also eat the caterpillars but first brush them repeatedly against the ground to knock off the hairs. Although many birds will eat the pupae, few species eat the hairly larvae to any extent. The exception to this is the cuckoo which is a hairy-caterpillar specialist and is often found in areas where there are tent caterpillar outbreaks. Overall, however, birds, including the cuckoo, can have little importance as mortality agents during outbreaks when populations of the caterpillars number in the millions. |

| |

|

|

|

| Sarcophaga aldrichi adult

fly |

Maggot of S. aldrichi

inside eviscerated pupa |

The parasitoid is often very abundant

during extended outbreaks |

|

Several years into an infestation the flies become extremely numerous and can become as bothersome to people as the caterpillars. As noted above, Jens Roland estimated the biomass of tent caterpillars during outbreaks in caribou equivalents. Likewise, he notes that the various species of parasitoid flies, of which S. aldrichi is the most abundant, may achieve a biomass per square kilometer of forest during the peak of a tent caterpillar infestation that is equivalent to that of 82 wolves . Right: S. aldrichi on a leaf wrapped around a cocoon of the forest tent caterpillar. |

The stinkbug (Pentatomidae) is a

generalist predator of caterpillars, killing its victim by

piercing and sucking.

|

|

Density independent mortality factors that limit population expansion of forest tent caterpillars are elements of weather, most importantly, temperature. Although the tiny caterpillars that are the basis for the next infestation spend the entire winter inside the shells of their eggs, they are rarely killed outright by extremes of temperature. Studies of the FTC in Somewhat counter intuitively, mild winters have the potential to do more harm to the caterpillars than cold temperatures. Indeed, the milder winter temperatures likely to become more prevalent with global warming could lead to the region-wide elimination of tent caterpillars, at least temporarily. This is the case because warmer winters can cause the caterpillars to emerge too early in the spring, well before the buds of their host trees have begun to expand sufficiently to allow the caterpillars to gain sufficient nutrition from them. In the spring of 2006 in central . |

|

| Condition of the buds of maple at the

time

forest tent caterpillars hatched. The caterpillars mined the buds

for food until the first leaves appeared. |

|

It is also the case that cool and cloudy spring weather kills caterpillars. Studies of the closely related eastern tent caterpillar have shown the when a tent caterpillar’s body temperature drops below about 59o F, the insect can not digest its food and will starve to death if it is maintained for long at that or a lower temperature. Although air temperature in the spring is often less than this threshold temperature, caterpillars bask in the sun to raise their core temperatures. However, basking is not possible if there is dense cloud cover, and a prolonged episode of cool, cloudy weather can lead to the death of the caterpillars due to starvation. .

|

|

Such

an event was

documented for the eastern tent caterpillar during the spring of 1917

in

|

Density

dependent and density independent mortality factors may interact to

bring a

population

explosion to a close. Thus, an epizootic

may sweep through a population of caterpillars,

precipitated by the cool and wet weather that favors the pathogen Furia. |

|

|

|

| Refoliation

of sugar maple: Left , June 9, 2006, Right, July 10, 2006 |

|

|

Filotas, M.J.F., A.E.Hajek, and R.A.

Humber. 2003. Prevalence and biology of Furia gastropachae

(Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales) in populations of the forest tent

caterpillar (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae). Can. Entomol. 135: 359-378.

Filotas, M. J., and A. E. Hajek. 2004. Influence of temperature and moisture on infection of forest tent caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae) by the entomopathogenic fungus Furia gastropachae (Zygomycetes: Entomophthorales). Environ. Entomol. 33: 1127-1136.

Fitzgerald,

T. D. and Costa, J. T. 1986.

Trail-based communication and foraging behavior of young colonies of

the forest

tent caterpillar Malacosoma disstria

Hubn. (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 79: 999-1007.

Fitzgerald,

T. D. and F. X. Webster. 1993. Identification and behavioral assays of

the

trail pheromone of the forest tent caterpillar Malacosoma disstria Hubner

(Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae).

Fitzgerald, T. D. 1995. The Tent Caterpillars. Cornell

University

Press. 303p.

For an extensive

database built around a recent forest tent caterpillar outbreak in

central New York State, click here.