| . |

Processionary Weevil

Phelypera

distigma

|

| Overview and Life History |

| Circular Formations |

| Trail

Making and Processionary Behavior |

| References |

|

Processionary behavior is a form of locomotion in which larvae travel together in single file, often in head-to-tail contact. While recent studies show that processionaries employ trail pheromones, contact stimuli associated with the bodies of siblings are essential to the initiation and maintenance of processions. Within the Insecta, processioning is known only from the social caterpillars and from the single species of weevil larva described here. In the Lepidoptera, it occurs most commonly in the subfamily Hemileucinae of the Saturniid and has been investigated in the genera Hemileuca and Hylesia. It is also particularly well developed in the Notodontidae genera Thaumetopoea and Ochrogaster. Sawfly caterpillars in the genus Perga are the only non-lepidopteran species previously reported to move together in procession-like formations but their behavior has yet to be studied. While processionary behavior is uncommon in the Insecta, many species of social insects engage in trail-based foraging behavior. Trail marking is ubiquitous among the ants (Formicidae) and termites (Isoptera) and has been reported from the social caterpillars of a number of lepidopteran and symphytan species as well. Despite the vastness of the Coleoptera and the great diversity of behaviors found among its members, it is noteworthy that the larvae of the curculionid weevil, Phelypera distigma (Boheman) is the first beetle shown to mark and follow chemical trails and to engage in processionary behavior. |

|

|

|

|

|

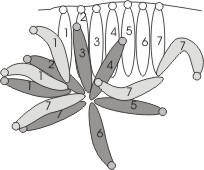

They larvae of Phelypera are highly social and are always in close contact. When they rest between bouts of feeding, they commonly arrange themselves in circular formations. It has been assumed that these "cycloalexic" arrangements function as antipredator defensive formations. The larvae of P. distigma readily bite and regurgitate when disturbed whether isolated or in groups. When cycloalexic formations consist of sufficient numbers of participants, the larva are protected from lateral attack but their lateral flanks are exposed in smaller aggregations and stink bugs are able to pierce larva and drag them from the assemblage. There appears to be no other significant predators or parasitoids and populations of the weevil are often very large.

Cycloalexic formations in P.

distigma may have coevolved with processionary behavior and

side-by-side leaf-margin feeding, both of which are orderly

arrangements of larvae. Indeed, it has been shown that circular

formations readily arise from and collapse into feeding

aggregations.

The adoption of a circular resting pattern places every member of the

colony in intimate lateral contact with other individuals and maximizes

the total amount of body contact possible in a two dimensional

aggregation. The arrangement allows a tactile signal arising

anywhere within the group to be transmitted from one individual to the

next and to rapidly radiate through the group. Thus, the entire

resting assemblage can be simultaneously alerted to the potential onset

of a bout of foraging or to the imminent formation of a procession by

even the smallest of tactile disturbances that precede these

events. Sawflies in the genus Perga are

processionary and also exhibit cycloalexy during the first three larval

instars when they are small enough for the whole colony to be

accommodated on the flat surface of a leaf. Cycloalexy and

processionary behavior, however, are not invariably linked, since the

processionary larvae of Hylesia. lineata do not arrange

themselves in circles even though they

often rest in the open on the surfaces of leaves. For more information on cycloalexic formations

see

references by Jolivet, et al.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Weevil

larvae, aligned head to tail in processions, physically stimulate the

tips of the abdomens of precedent individuals with their heads to

promote the forward locomotion of the assemblage. Tactile or

chemotactile stimuli found at the tips of the abdomens

of larvae in processions also serve to stimulate following

behavior. Thus, tactile stimuli appear to promote

processionary behavior

both by drawing larvae forward from the front and by nudging them

forward

from behind. However, since isolated larvae of P. distigma

readily follow lures made from the eviscerated abdomen of a larva,

tactile stimuli applied to the tip of the abdomen are not essential to

the elicitation of locomotion. |

|

|

When the larvae of P. distigma move from an old to a new

site

they typically travel in subgroups with stragglers sometimes not

arriving at the new site until as long as an hour after the arrival of

the initial contingent. Thus, trail pheromones subserve

processionary behavior by allowing stragglers to catch up with colony

mates that have gotten ahead of them. Fragmentation of colonies

into permanently isolated subgroups would likely occur in the absence

of the trail pheromone. |

|

Costa, J. T., Fitzgerald, T. D., Pescador-Rubio, A., Mays, J., and Janzen, D. H. 2004. Group foraging behavior of larvae of the Neotropical processionary weevil Phelypera distigma (Boheman) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Hyperinae). Ethology in press.

Fitzgerald, T. D., A. Pescador-Rubio, M.

Turna, and J. T. Costa. 2004. Trail making and

processionary behavior of the larvae of the weevil Phelypera

distigma (Coleoptera:

Curculionidae). J. Insect Behavior in

press.

Jolivet, P., Vasconcellos-Neto, J., and Weinstein, P. (1991). Cycloalexy: A new concept in the larval defense of insects. Insecta Mundi 4: 133-141.

Jolivet, P., and Maes, J. M. (1996). A

case

of cycloalexy in a curculionid: Phelypera distigma

(Boheman)

(Hyperinae) from Nicaragua. L’ Entomologiste. 52: 97-100.